JEO 4 - Japan’s High Tech Labor Pains

A monthly news roundup and a deep-dive on Japan's STEM Labor Workforce.

Welcome to Japan Earth Observer (JEO), a free monthly newsletter with a news roundup and one in-depth article about the space, Earth observation and geospatial industries in Japan. In addition to a news roundup, in this edition I’m also going to write a bit about demographic and labor market challenges that Japan faces in its attempts to grow the industry.

News & Announcements

💱 Contracts and Funding

- SKY Perfect JSAT has signed a second contract with Thales Alenia Space to build and deliver the JSAT-32 [SpaceNews] communications satellite. The 3.7 ton satellite will operate Ku- and Ka-band broadband and broadcast services in geostationary orbit over Japan and the Asia-Pacific region. Delivery is aimed at a 2027 launch and will use the Spacebus 4000B2 bus.

- Synspective has signed a contract with SpaceX for two of its StriX satellites to be launched on a rideshare in 2027. The announcement does not indicate if this will be a Transporter (sun-synchronous orbit) or a Bandwagon (mid-inclination orbit), but this appears to be on top of the 10 dedicated launches already signed with RocketLab for 2025 to 2027. Is Synspective hedging its launch vehicle bets or accelerating its buildout? Is SpaceX just cheaper? Or is the RocketLab launch schedule constrained in some way?

- U.S. space station startup, Vast, is seeking investment partners in Japan. CEO Max Haot visited Tokyo in February to meet with potential minority investors for the Haven orbital space stations [Nikkei Asia] they are developing. Vast is playing catch up. The Mitsui & Co trading house invested in Axiom Space in 2021; Kanematsu contributed funding to Sierra Space in 2022; and Mitsubishi bought a stake in Starlab last year. While it got a late start, Vast may pull ahead with its first space station module, Haven-1, currently expected to launch in May 2026. All of these firms are racing to replace the capabilities of the International Space Station (ISS), which is expected to be de-orbited around 2030.

- ispace stuff:

- ispace and SpaceData signed an MoU to collaborate on creating a high precision digital twin of the lunar surface [ispace]. By developing a detailed topographical model of the Moon, the two companies hope to be able to carry out physical simulations of lunar surface conditions in order to reduce costs and risks of lunar exploration mission.

- ispace received an additional US $7.7 million from Draper under the NASA CLPS CP-12 contract to support development of the ispace-US APEX 1.0 lunar lander. This lander is considered “Mission 3” by ispace and is planned for a 2026 launch.

- ispace also signed a contract with Kurita Water Industries to transport a water processing system to the lunar surface to conduct demonstration tests on an ispace lunar mission after 2027. The ability to purify water on the lunar surface promises to reduce the cost of supporting a future lunar base.

- Space Strategy Fund details are starting to trickle out. I wrote a deep dive on the JPY 1 trillion JAXA-administered fund a few weeks ago. The RFPs starting being issued in July 2024 with almost all of the initial awards announced by February this year. However, while funding recipients were made public by JAXA, the funding amounts and award periods were not. That’s starting to change, and the publicly traded companies, at least, are sharing additional details. The Space Strategy Fund has three major priorities - transportation, satellites, and exploration - and the following two awards fall under a satellites sub-theme called “accelerating the construction of commercial satellite constellations” (商業衛星コンステレーション構築加速化).

- The Q-shu Pioneers of Space (iQPS) initial block of funding will be JPY 8.465 billion (~US $56 million) and will run through March 2027 [in Japanese] (implementation work may continue to March 2029), and this first tranche could increase based on achievement of milestones. iQPS has indicated that they have already begun manufacturing on satellite #18. Current manufacturing will continue to be self-funded, and they will use the new funding to subsidize development, manufacturing, and launch costs starting with satellite #22.

- Synspective, an iQPS rival aiming to build a SAR constellation of 30 birds by the late 2020s, will receive an initial Strategy Fund tranche of JPY 16.464 billion (~US $110 million) and will also run through 31 March 2027. Similar to iQPS, implementation may continue to March 2030, and the first batch of funding may be followed by additional funds if hit specific milestones.

- Speaking of the Strategy Fund, JAXA has announced the 2025 themes [in Japanese]. The full 2025 solicitation cycle will include 24 themes (up from 22 last year) across the three main priority areas: transportation (5 themes); satellite tech (11 themes); exploration (5 themes); and cross-cutting topics (3 themes). JAXA says they will post an RFP announcement about a month prior to posting for formal RFPs. Applicants will have about 6-8 weeks to prepare proposals. Formal RFPs for the first three themes will include: 1) rocket components contributing to high frequency launch schedules; 2) feasibility studies for satellite buses and optical communication terminals for satellite optical communication; and 3) foundational technology for constructing lunar infrastructure. JAXA is organizing in-person information sessions for each priority area in April [in Japanese]. Drop me a line if you would like the full list of themes in English.

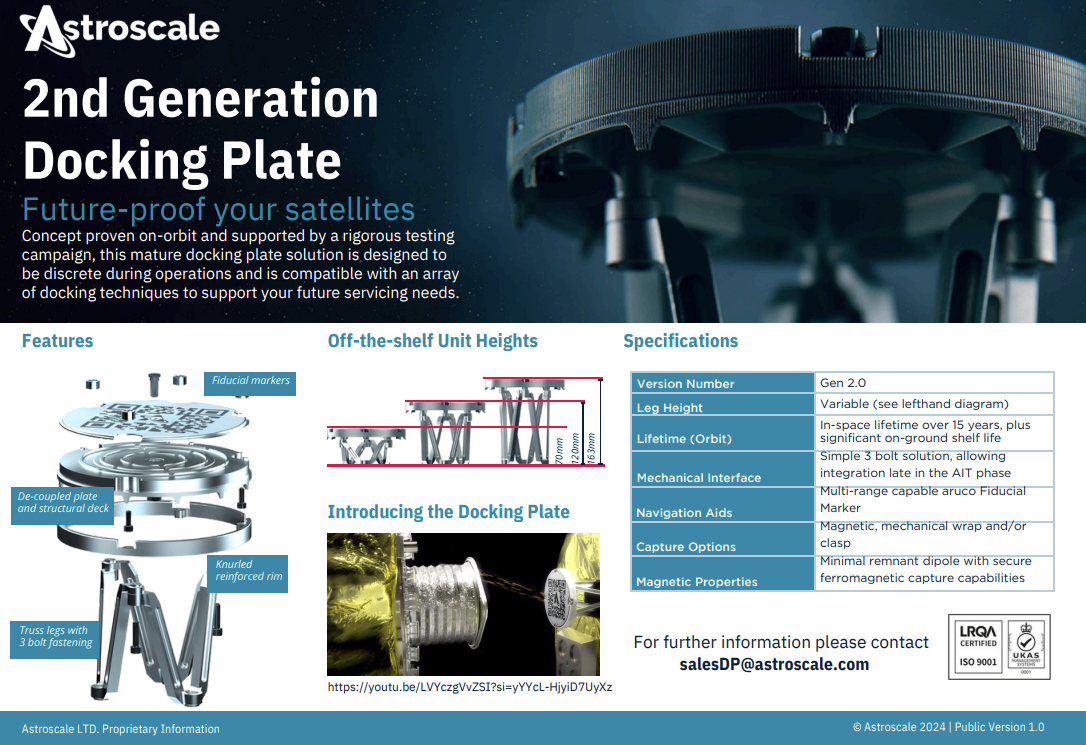

- Astroscale UK won the first commercial sale of its Docking Plate (DP) technology with an order for a minimum of 100 of its second generation plates by Airbus for delivery through June 2026. Citing a confidentiality agreement, Astroscale did not disclose any additional details about the Airbus deal, but Airbus Defense and Space signed the ESA’s Zero Debris Charter in 2024, and this deal represents a concrete step toward realizing this commitment. A second generation docking plate was launched on a customer satellite for the first time with the SpaceX Transporter-12 mission [Astroscale] on 14 January. In a 14 March earnings call, Astroscale shared that its standardized docking plates are now flying on 569 satellites [Astroscale see p. 10]. These standardized docking plates have been developed based on experience gained in the ELSA-d and ADRAS-J missions, are designed to last at least 15 years, support both magnetic and robotic arm docking, and have been tested to endure radiation, UV exposure, vibration, and shock.

- A standardized docking plate is a great example of a decidedly non-flashy technology that could have an out-sized impact in reducing orbital debris if it is widely used. But the key to a successful standard is broad adoption, and I wonder if Astroscale has considered licensing or even open sourcing the hardware design in order to further encourage use on every satellite or rocket body sent into orbit.

- Another satellite servicing company, Orbit Fab, is focused on refueling missions and is making a similar play to Astroscale by installing its RAFTI refueling ports on new satellites. Interestingly, the RAFTI design is released under an open license, defining the mechanical, electrical, and functional specifications for the ports such that other companies could manufacture them.

Astroscale’s second generation docking plate mounted on a satellite loaded for hhe SpaceX Transporter 12 rideshare. Credit: SpaceX

🛰️ Technology and Infrastructure

- Tellus will start providing data from the GOSAT and GOSAT-2 satellites through a web application in March 2025. Tellus already provides a range of Japanese government data through both an API and its Traveler web UI. The two Greenhouse Gas Observing Satellites (GOSAT), also known as Ibuki and Ibuki 2 (いぶき and いぶき2号) have been flying since 2009 and 2018, respectively, and each mounts two sensors for greenhouse gas detection and cloud/aerosol detection. The GOSAT data has been distributed since 2008 by the Ministry of the Environment (MOE) through the National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES) in a specialized format, and the Tellus distribution is expected to make it more accessible. MOE is also expanding use of the GOSAT satellites by using them to track greenhouse gases in Central Asia [Nikkei Asia], including: Mongolia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, with Turkmenistan being added in 2026.

- iQPS added a new synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellite to its constellation with a dedicated RocketLab launch [SpaceNews] on 14 March. QPS-SAR-9 (nicknamed SUSANOO-I or スサノオ- I) is the first of eight contracted iQPS launches with RocketLab with six planned for 2025 and two in 2026.

- Axelspace announced that they’ve been able to recover control of their GRUS-1E microsat [Axelspace] which lost attitudinal control on 20 December 2024. The 55kg optical bird is part of a five-satellite constellation.

🔭 Science

- A joint project led by Professor Kawanishi Tetsuya at Waseda University and the Sensor Research Group at JAXA has successfully tested a prototype wireless communications system with a 4 Gbps transmission speed over 4.4 km distance using the 95 GHz band [JAXA]. Currently most air-to-ground and orbit-to-ground communications links operate on either the X-band (8 GHz band) or Ka-band (26 - 40 GHz), but data transmission in these bands is limited to a few hundred Mbps to several Gbps. By using high altitude platform stations (HAPS) or aircraft flying at 20km or less, multiple channels in the terahertz range (92 GHz - 104 GHz) can be combined to achieve high capacity data transmission in excess of 20 Gbps. Future research will focus on increasing the transmission distance to 20 km, increasing transmission speed of 20 Gbps, and improving antenna tracking capabilities for flying objects. This research is aimed at providing airborne high speed regional networks for mountains areas and remote islands as well as supporting ad hoc networks in disaster scenarios.

🗺️ International Collaborations

-

The SpaceX Crew Dragon-10 successfully launched on March 14 [SpaceNews] from Kennedy Space Center Pad 39A carrying two U.S. astronauts, a Russian Cosmonaut, and a veteran JAXA astronaut Onishi Takuya (大西 卓哉) to the ISS and docked early on March 16 [Space.com] for an expected six month mission. Onishi has been a JAXA astronaut since 2009 and previously spent 115 days at the ISS in 2016 as part of Expedition 48/49. Before being selected as a JAXA astronaut in 2009, he was a pilot for All Nippon Airways.

-

The SpaceX Crew Dragon-11 roster has been announced and it includes Yui Kimiya (油井 亀美也), a veteran JAXA astronaut that will be returning to the ISS for the second time. His previous trip was for 142 days in 2015 as part of Expedition 44/45, when he directed the arrival of HTV-5 JAXA resupply ship, carried out two spacewalks and did experimental work on the Kibo module. Before his career as a JAXA astronaut, he was a test pilot and later Lieutenant Colonel in the Japan Air Self-Defense Force.

-

Synspective has set up two new U.S. subsidiaries, a holding company and an operating company. The new subsidiary will be aimed at selling Synspective’s SAR imagery into the North American and Latin American markets and will be run by Dr. Kumar Navulur, who is also on the Board of the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC).

-

Expo Osaka 2025, opening on 13 April, will have a USA Pavilion that will feature space exploration milestones and highlight U.S.-Japan collaboration in space [U.S. State Dept] with a theme of “Imagine What We Can Create Together.” That theme rings a little hollow in light of the recent tariff announcements, but if you want to learn more there is a web site. This expo has been plagued by budget overruns, construction delays [Nikkei Asia], conflict, and controversy, and ticket sales have been tepid so far [Japan Times]. That stands in stark contrast to the 1970 Osaka Expo (大阪万博), which was an astonishing triumph. It was the first international expo held in Asia, and almost 65 million people attended, an attendance record that was not surpassed until the 2010 Shanghai Expo. It was also the rare expo that turned a profit, and its site, the Expo ‘70 Commemorative Park remains popular with a range of museums, a stadium, and gardens. No such high-minded aspirations are on deck for the 2025 Expo site, which will be turned into Japan’s first casino.

Aerial view of Expo Osaka USA Pavilion Credit: U.S. State Department -

Axelspace and Synspective provided satellite imagery to UN-SPIDER for earthquake damage assessment in Myanmar. Unfortunately, unlike some of their EO competitors, neither company operates an open data program. Nor was I able to find a formal disaster response policy or program. So if anyone wanted to use the data to support disaster response (for example, the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team’s Myanmar mapping effort), they would likely have to go through UN-SPIDER. That seems like a lost opportunity for both firms as well as the collective response effort.

Synspective SAR image of collapsed Myanmar bridge. Credit: Synspective -

Japan-India Collaboration

- Astroscale announced partnership agreements with Digantara and Bellatrix Aerospace in India [Reuters]. Astroscale will gain access to the rapidly growing India market through the new partners, who will likewise gain access to the Japan market. Digantara provides orbital monitoring services (space situational awareness) and Bellatrix makes satellite propulsion systems. The partnership announcement does not include financial terms, but presumably the partners will team to bid on contracts together.

- Skyperfect JSAT-spinoff Orbital Lasers made a similar agreement with InspeCity in December. Orbital Lasers is testing technology that can be mounted on satellites like InspeCity’s and used to ablate surfaces on a spinning satellite in order to stop the spin and make it easier to deorbit.

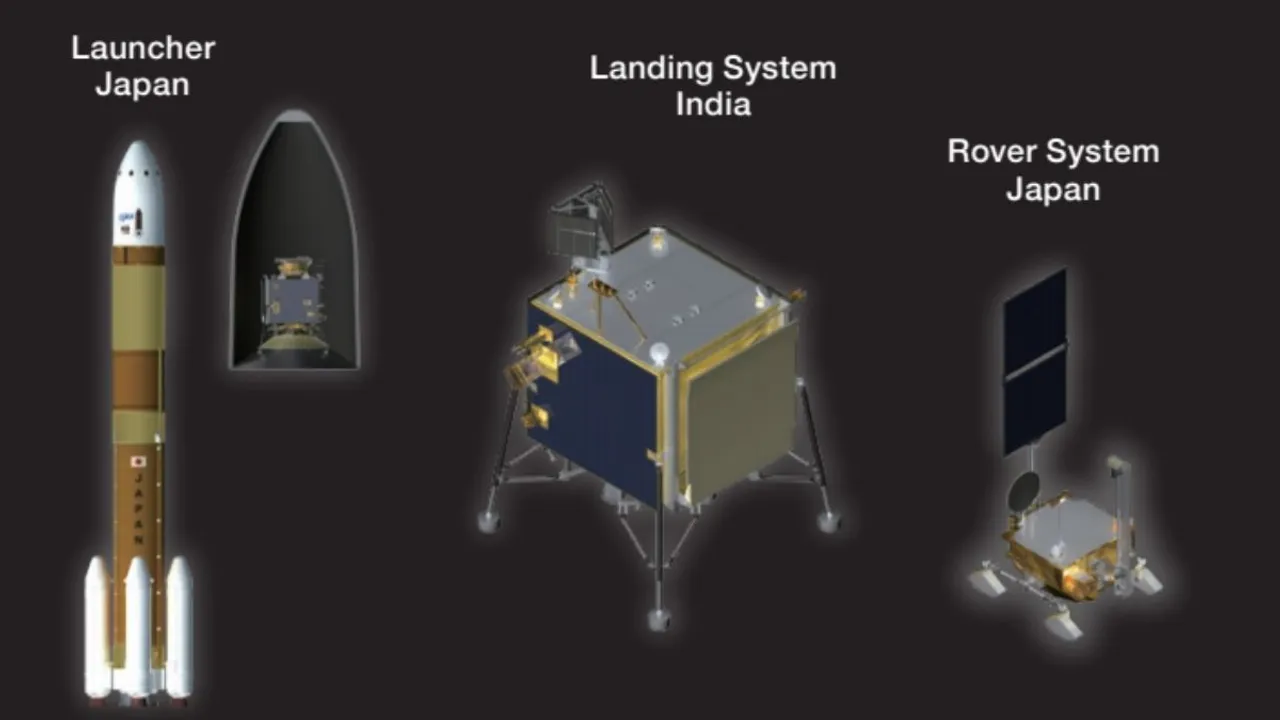

- Funding for the ISRO-JAXA Chandrayaan-5 mission has been approved by the Indian government [The Hindu]. Also known as LUPEX, the mission will deliver a 350 kg rover to the permanently shadowed south pole region of the lunar surface to search for water sources. JAXA is expected to provide the H3 rocket to launch the probe from Tanegashima in 2028-2029. The lander will be built by ISRO, and the rover will be developed by JAXA for a planned 100 day mission. There will be 10 science payloads: five from JAXA, three from ISRO, and one each from NASA and ESA.

Design renderings of Lupex mission. Credit: JAXA

📆 Asia-Pacific Conferences & Events

This newsletter is mostly focused on Japan, but I also like to highlight events across the Asia-Pacific region as well. Some upcoming conferences include:

April 2025

- Locate25 - 6 - 10 April - Brisbane, Australia

- International Conference of Deep Space Sciences - 7 - 11 April - Hefei, Anhui, China

- CSIS Webinar: Deepening the U.S.-Japan Space Security Relationship - 11 April, 1p - 4p ET, Washington DC, United States

- Apophis T-4 Years: Workshop on Planetary Defense - 9 - 10 April - Tokyo, Japan

- Drones and Uncrewed Asia - 9 - 10 April - Singapore

- GEO Connect Asia - 9 - 10 April - Singapore

- Earth Observation Data Use Business Community (BizEarth) (地球観測データ利用ビジネスコミュニティ) - 21 April - Tokyo, Japan

- 10th China Space Day - 24 April - Shanghai, China - marks anniversary of China’s first satellite launch, Dongfanghong-1 in 1970

- 3rd Machine Learning for Remote Sensing (ML4RS) Workshop - 27 April - Singapore

- Cloud Native Geospatial (CNG) Conference - 30 April - 2 May - Snowbird, Utah, United States - this conference isn’t in the Asia-Pacific region, but it’s a unique event for which there isn’t yet a regional equivalent

May 2025

- Global Space Exploration Conference (GLEX) - 7 - 9 May - New Delhi, India

- GeoSpace Bharat - 14 - 16 May - Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India

- Langkawi International Maritime and Aerospace Exhibition (LIMA) - 20 - 24 May - Subang, Selangor, Malaysia

- Australian Space Summit and Exhibition - 27 - 28 May - Sydney, Australia

- Satellite Asia 2025 - 27 - 29 May - Singapore

June 2025

- APSAT International Conference - 2 - 3 June - Jakarta, Indonesia

- International Space Summit - 3 - 5 June - Daejeon, South Korea

- 9th Shanghai International Aerospace Technology and Equipment Exhibition - 11 - 13 June - Shanghai, China

- India Space Congress - 27 - 27 June - New Delhi, India

- UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) 25 June - 4 July - Vienna, Austria

- 37th Space Studies Program (SSP) - 30 June - 22 Aug - Ansan, Gyeonggi, South Korea

July 2025

- 43rd Aerospace Numerical Simulation Technology Symposium - 2 - 4 July - Tokyo, Japan

- Spacetide - 7 - 10 July - Tokyo, Japan

- 35th International Symposium on Space Technology and Science (ISTS) & 14th Nano-Satellite Symposium (NSAT) Joint Symposium - 12 - 18 July - Asti Tokushima, Japan

- 18th Australian Space Forum - 15 - 16 July - Adelaide, South Australia, Australia

- IEEE Space - 21 - 23 July - Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

- SPEXA Space Business Exp - 30 July - 1 Aug - Tokyo, Japan

It’s not really a conference but Synspective is offering a free webinar on using SAR images with QGIS. You can sign up at https://synspective.com/on-demand-class-2/2025/qgis_ondemand/.

Japan’s High Tech Labor Pains

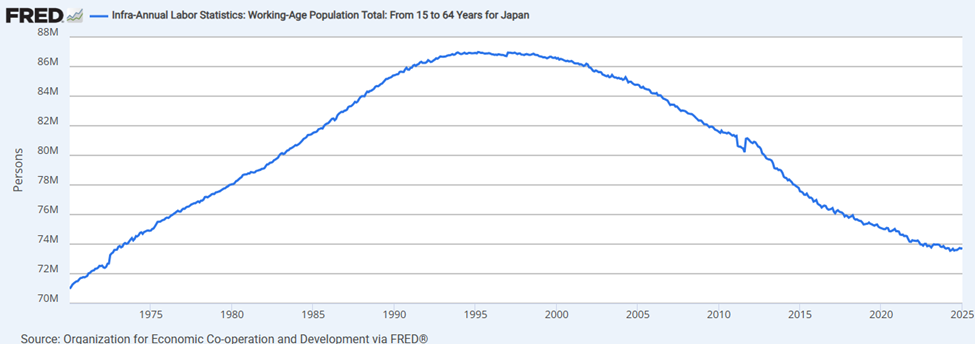

Even a casual observer of Japan will have likely learned that it faces significant demographic challenges. A steep fall in the birth rate and long life expectancies have combined to create a decline in both the absolute population and the working age population.

Japan’s working age population 1970-2025. Credit: OECD

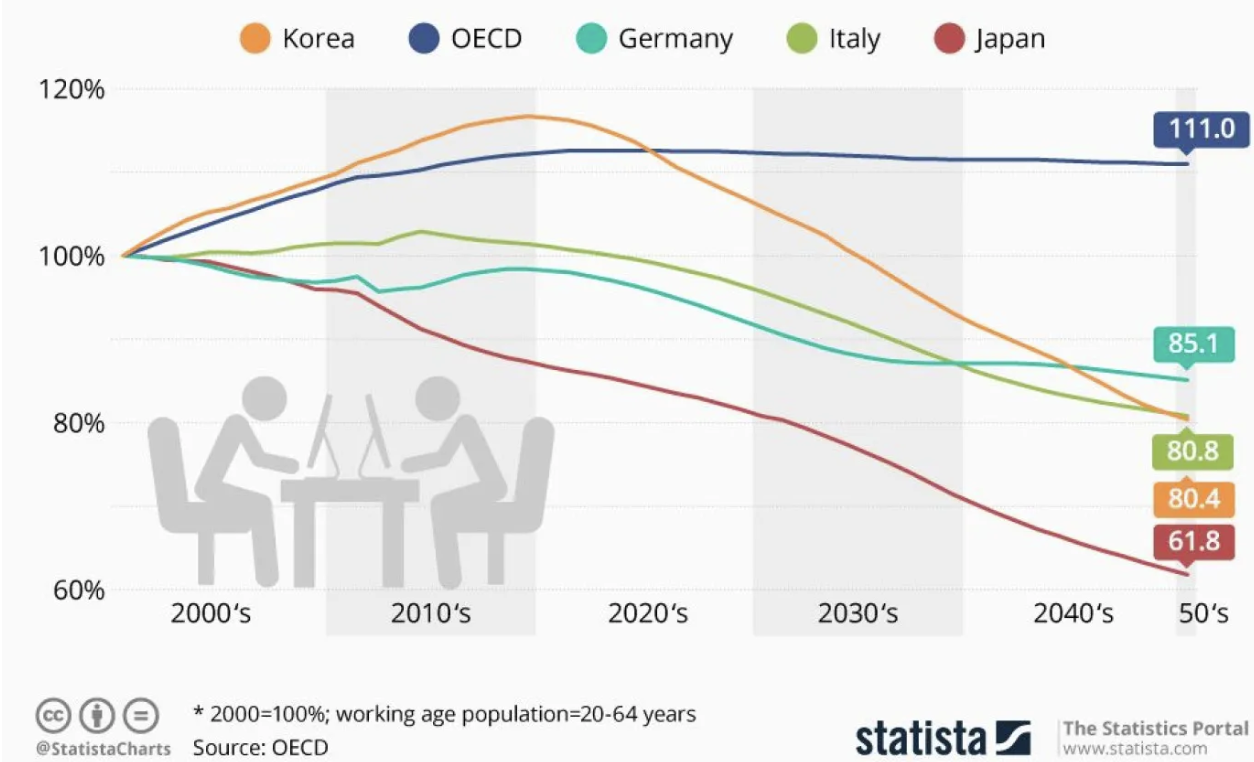

The numbers are stark. In 2024, fewer than 721,000 babies were born out of a population of 123m. That is 5% fewer than the previous year and the ninth straight year of decline. Despite those long lives, deaths now outnumber births by more than two to one. Other advanced economies, like South Korea, Germany, and Italy also face declining working age populations, but while South Korea has even lower birth rates than Japan’s today, it only began its population decline in 2020, while Japan’s began in the mid-1990’s. By 2050, Japan’s working age population is forecast to be only 60% of its peak in 1995.

Working age population projections 2000-2050. Credit: OECD/Statista

The working age population really matters because the taxes paid by the working population fund support for the growing cohort of elderly. By 2030, one person in three will be over 65. There are a myriad of reasons for the low birth rate: inflexible family laws, low financial support for child care, few child care facilities, expensive schooling, and fewer women choosing to marry and raise families. For example, while parental leave laws appear generous on paper (both parents are eligible for a minimum of one year of paid leave), in actual practice mothers often lose their jobs, and a mix of company policy and social/cultural pressure mean that many fathers may only take a week or two of leave. A recent survey suggested that 52% of young people do not want to have children [Unseen Japan]. Some pioneering cities, like Akashi in Hyogo prefecture (west of Kobe) and Nagareyama outside Tokyo, have implemented long-term policy changes that have aimed to radically improve public services for families raising children [The Economist]. These cities have seen significant population growth as a result, but they remain the exception and fundamental policy changes at the national level still seem far off.

Japan population pyramids for 1950, 2005, and 2055. Credit: Japan National Institute of Population and Social Security Research

Chronic labor shortages

Japan now faces chronic labor shortages in almost every industry with two-thirds of employers indicating they have too few workers [Reuters]. While there have been a range of policy responses, government policy often reflects contradictory priorities. For example, in an effort to reduce accidents and improve working conditions for truck drivers, restrictions on overtime were implemented in April 2024. This created a huge shortage of truck drivers, significantly reducing transportation capacity and snarling logistics across the country. A shortage of construction workers has caused delays and budget overages on projects across the country, and agriculture, manufacturing, health care, and other industries all face chronic understaffing.

The labor shortage is not limited to blue collar jobs like transportation, construction, and manufacturing. With the shift to EVs and self-driving vehicles, software has become as important as manufacturing expertise, and Japanese carmakers now face an estimated shortage of 33,000 software professionals this year [Nikkei Asia]. Japan is aiming to significantly expand the space economy and is attempting to shift from a relatively centralized workforce employed by government agencies and large corporations to a more diverse and dynamic industry structure that includes hundreds of small- and mid-sized ventures. The JPY 1 trillion Space Strategy Fund is helping to make this possible, but at the Spacetide conference in July 2024, every speaker from a Japanese space company cited workforce shortages as a significant challenge. The Astroscale CEO, Okada Nobu, estimates that Japanese universities only graduate about 50 space engineering students [Payload] annually and building a company that can compete on the world stage will require AI, software, sales, marketing, and product managers, and it’s not clear that the domestic workforce will be sufficient.

Responses to the labor shortage

Given the broad concerns about labor shortages across all science, technology, and engineering roles, you would imagine that the government would be doing everything possible to both recruit and retain research and engineering talent. There are, indeed, many government policies and initiatives aimed at recruiting people for roles in high demand as well as a range of complementary industry responses.

Expand the workforce

If you don’t have enough workers, the most obvious step would be to increase the number of workers. Unemployment in Japan is very low, and the labor force participation rate is already among the highest in the world [OECD], clocking in at 81.7% (76.2% for women and 87% for men) of adults aged 15-64. But Japan also has some of the healthiest senior citizens, so why not encourage those healthy elderly to keep on working? While France went through convulsions trying to raise the retirement age from 62 to 64, Japan implemented a new law in 2021 that effectively raised the retirement age from 65 to 70 without significant backlash. Employees are not required to work to that age, but employers are strongly encouraged (with some financial incentives) to offer one of several options to make it possible to continue working up to age 70, though not necessarily at the same salary and working conditions.

Immigration

Another obvious path to expanding the workforce is to fling open the doors to potential immigrants. Japanese public opinion toward immigration has long been ambivalent. Many Japanese recognize the need for immigration to deal with labor shortages, and some welcome the greater cultural diversity and revitalization this might bring. However, there is general anxiety around the potential impact of large-scale immigration [Univ. of Tokyo]. Many people associate immigrants with higher crime rates, and there are concerns about impacts on social cohesion and the culture. In general, most people view immigrants as “guests” rather than permanent members of society that will be integrated over the long term.

While the government has not pursued policies that would allow large-scale immigration, the numbers have steadily increased for the past two decades and are expected to continue rising in the decades to come. The number of foreign residents in Japan reached 3.77 million in 2024 [Nikkei Asia], increasing by 10.5% in a single year. Visas for skilled worker programs rose by 36.5% since 2023 and so-called “highly skilled professionals” were up by 19.8%. There are also more flexible conditions for digital nomad and entrepreneur visas. While foreign residents from China outnumber every other country, much of the recent increase is from Vietnam, Nepal, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia. These increases are not necessarily coordinated actions between government and industry, but there are explicit government policies aimed at increasing foreign direct investment and skilled technology workers from India and Southeast Asia [Nikkei Asia]. Japanese universities actively recruit foreign students and there is often a path to employment following graduation. Further, if a Japanese company wants to hire a highly skilled foreign worker, the process of acquiring a visa is relatively straightforward (I make this statement as a former employer and sponsor of advanced technology visa holders in the United States, where the process is extraordinarily bureaucratic, time-consuming, arbitrary, and expensive).

Improve working conditions

If there are not enough tech workers, an obvious strategy would be to provide better salary and working conditions in order to both attract new folks and retain the ones you have. While after 30 years of a flat economy, salaries in Japan are now below those in Europe and North America, and for the researcher, scientist, and technology roles, China and other parts of Asia have emerged as key competitors for the most talented workers. But there are some signs of upward movement on salaries, and more than half of office workplaces in Japan support hybrid or fully remote positions [Nikkei Asia]. Carmakers that are struggling to recruit software engineers for the EV and self-driving future [Nikkei Asia] are building attractive new offices in downtown Tokyo, replacing seniority pay scales with ability-based systems, abolishing mandatory retirement and recruiting mid-career professionals in India and Vietnam.

Formalize space industry career paths

Following the lead of cybersecurity, IT, and other advanced technology roles with constrained labor supplies, the Japanese government is developing a set of standards to support career transitions to the space industry [Nikkei Asia]. The new standards are being developed by JAXA and industry leaders and aim to clarify the skills being sought for the dozens of job categories involved in rocket and satellite development roles. The standards will also be used by universities to develop programs and curricula necessary to attract and train young professionals. While space industry workforce concerns are less pronounced in the United States, industry leaders have called for similar measures to develop structured career pathways [SpaceNews] in order to grow the workforce.

Build offshore outposts

I have been surprised by the number of Japanese space companies that open subsidiaries in Europe and North America at a much earlier stage than I would have expected. Astroscale already has offices in Israel, France, the UK, and the U.S., and ispace has outposts in Denver and Luxembourg. I think there are likely a number of reasons for this pattern. First, the domestic Japanese space marketplace is too small to reach the scale to grow and innovate at a speed necessary to be globally competitive, and opening an EU, UK, or North American subsidiary is a way to access the much larger customer markets in these regions. Second, the space industry remains highly reliant on governments as both a customer and R&D funding source, and governments are universally reluctant to fund R&D efforts occurring outside their borders. Third, rocketry and satellites always have national defense and intelligence applications, and export control regulations often require work to be performed domestically. Finally, though, and most relevant to the labor topic, opening a subsidiary in bigger labor markets provides access to a much larger pool of talent.

Precarious careers from good intentions

Above, I outlined a raft of tactics that the government and industry have been using to grapple with a very difficult workforce capacity challenge. However, other policy efforts have ended up having unintended and pernicious consequences that have been damaging and counterproductive. For the research, science, and technology communities, the single greatest recent disruption has been the delayed effects of a labor law reform enacted in 2013, during Prime Minister Abe’s administration. To understand the origins of this issue, I will have to delve a bit into both some history and some unique characteristics of labor conditions in Japan.

Many people outside Japan have an image of Japanese workers joining a company after high school or university and then maintaining a lifetime employment relationship with a single company until retirement. However, this lifetime employment system and the archetypal salaryman, while real, has never represented all workers in Japan, and the number of so-called “regular employees” has been declining since the 1990s.

Japan essentially has a two-track employment system. Regular employees (正社員 or 正規雇用) are usually recruited when they finish their schooling and tend to remain with a single employer for much of their working career. These positions have a great deal of job security; termination is possible but legally challenging. Regular employees must be provided with a range of mandatory social insurance benefits - health, pension, and unemployment - as well as retirement allowances, family allowances, bonuses and access to supplementary perks such as support for housing and commuting expenses. They generally enjoy higher social status and receive bonuses as well as structured, annual salary increases based on seniority. It is a bit like being a tenured professor at a university in North America. However, in exchange for permanent employment, higher pay, benefits, and status, employer expectations are almost unbounded; the employee may be expected to work hours, transfer to another company location, and other demonstrations of commitment to the organization. The relationship is sometimes described as “membership-based” employment (メンバーシップ型雇用), rather than “job-based employment” (ジョブ型雇用). Often a regular employee is not hired for a given set of skills, but rather to become a long-term member of the employer organization and may take on many different jobs over the course of a multi-decade career.

Non-regular employees (正社員以外 or 非正規雇用) is a broad category that includes temporary workers (アルバイト), part-time (パートタイマー), workers dispatched by temp agencies (派遣社員), fixed-term contract employees (有期契約社員), task-based (or “entrusted”) contract employees (契約社員), and miscellaneous other forms of employment. There are stark gender- and age-based differences. Most regular positions are occupied by men, and while female workforce participation has risen the past several decades, the increase is primarily in non-regular employment. For workers age 65+, 77% are non-regular employees. Pay for non-regular employees is usually lower. On average, non-regular employees received about 67% of regular employees, but seniority-based pay for regular employees means that the discrepancy rises over time and while it may be 10-20% wage gap for a young person, it rises to a 50% difference for a worker in their 50s [Japan CAO]. The pay discrepancy is notwithstanding the fact that non-regular employees often work alongside regular employees, performing the same work. Non-regular employees working more than 20 hours per week receive social insurance benefits (unemployment, health, and pension insurance), but they generally do not receive other benefits, opportunities for career advancement, bonuses, or pay increases.

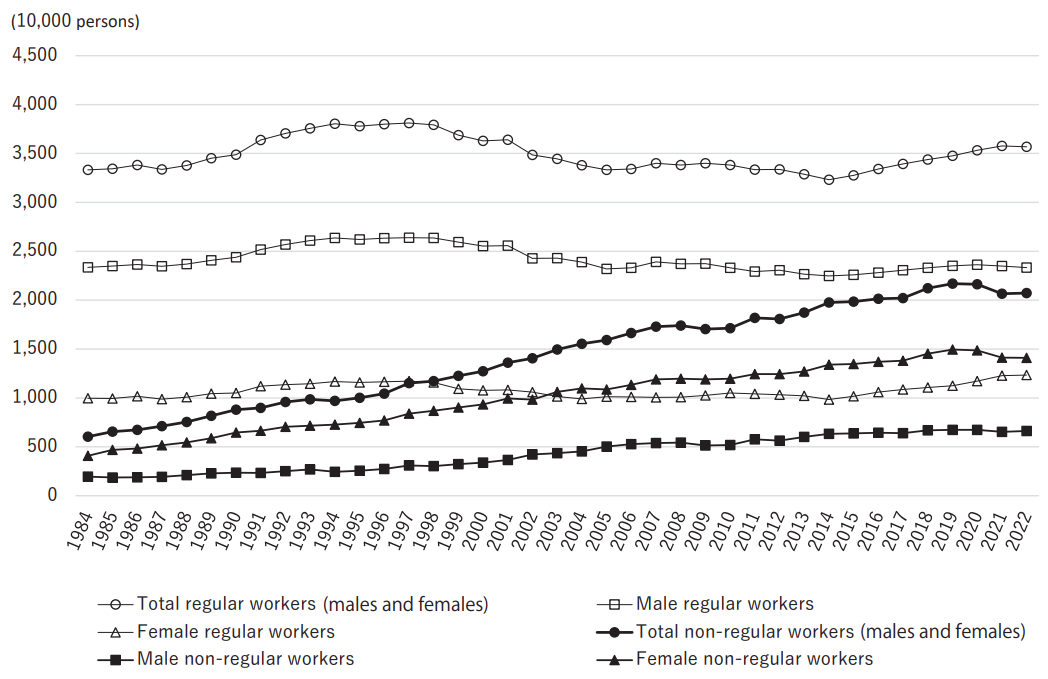

The number of regular employees rose with population growth until the early 1990s. The bursting of the real estate asset bubble in 1993 marked the beginning of a multi-decade economic stagnation. The ruling LDP party implemented a series of laws deregulating the labor market, effectively making it easier for employers to shift people from regular to non-regular employment [APJJF]. All of those permanent employees and their benefits were expensive, and employers subsequently reduced the number of regular employees, and the number of non-regular employees rose from 16.4% of the workforce in 1985 to 36.7% in 2022. The 2008-2009 financial crisis saw many temporary employees abruptly lose their jobs and public pressure grew to make employment less precarious. A series of labor law reforms were subsequently enacted from 2007 to 2022, effectively re-regulating the labor market and encouraging employers to shift more employees into regular employee status. Here’s a graph summarizing the changes over the past 40-odd years [Takahashi], with breakdowns by gender.

Trends in regular and non-regular workers. Credit: Takahashi Koji, “Non-regular employment measures in Japan”, Japan Labor Issues, Autumn 2023.

Those labor market reforms that started in 2007 have worked…kinda. The number of regular employees has indeed started rising again. Further, more non-regular workers are now covered by social safety net provisions, like unemployment, health, and pension insurance. However, significant wage gaps remain [Takahashi]. Investment in on-the-job training that might help workers advance their careers is actually falling [Japan CAO], and some efforts to mandate conversion of long-term employees to regular status have had the opposite effect. And none of the new reforms cover freelancers or platform (gig) workers.

Ok, so that was a quick thumbnail sketch of the labor market. You are probably wondering what this has to do with the space industry, or, more broadly, STEM workers in general. Enter the Revised Labor Contract Law of 2013 (改正労働契約法). This well-intentioned reform mandated that non-regular employees with fixed-term contracts could apply to become regular employees after 5 years. If they were researchers, then the time limit was 10 years. Essentially, if you are employing someone on fixed contracts for more than five (or ten) years, you won’t be able to keep doing that indefinitely and avoid providing them the benefits, raises, and job security you give to your regular employees. This was called the “Indefinite Term Conversion Rule” (無期転換ルール). Sounds good, right? Well, it hasn’t quite turned out that way. All of those benefits, job security, and extra pay are expensive, so instead of allowing workers to convert to regular employment (and raise their costs), many employers are simply firing people shortly before the five or ten year time limit arrives. Japan’s government R&D funding to universities and national labs has grown rapidly since the mid-1990s. That seems like good policy: the real estate bubble burst, and the economy is in the crapper, so you invest in research and infrastructure (the future). Japan doubled government research spending in 5 years. As the research projects proliferated, new researchers were hired under fixed-term (non-regular) contracts. This gave the research institutions a lot of flexibility - theoretically, if a research project lost its funding, they could cut the researchers loose - but in reality, most fixed-term employment contracts were renewed indefinitely.

Then this new Conversion Rule arrives in April 2013. If you are a researcher, you might initially be really happy; if you work hard on your research for 10 years, you will win regular (permanent) employee status, right?. But then in early March 2023, you receive notice that you have been fired instead, just weeks before you could request the conversion. And that is exactly what happened in universities and research labs across Japan. Further, for new research hires since 2013, almost no one receives a contract that will exceed 10 years.

As an example, RIKEN, the National Science Lab (理化学研究所), was a significant beneficiary of the growth in research funding. In the mid-1990s, RIKEN had 400 employees, most of whom had regular status. By 2022, RIKEN had grown to 2,893 workers [Science], but 77% of them were fixed-term (non-regular) workers. When the 10 year limit was reached in March 2023, some researchers were given regular status, but out of 203 subject to the 10-year rule that year, 97 were terminated [Tokyo Shimbun]. An additional number were demoted. Another 87 people left because their team leader had been terminated and the research team disbanded. By October 2024, it was reported that 1 in 8 researchers had lost their jobs [Mainichi Shimbun] and the ripple effects extend well beyond the people directly affected. Almost 60% of researchers in Japan say that they have been negatively affected by the Conversion Rule. Many people that lost their jobs have had offers for similar roles at higher pay in China, Korea, and Taiwan. Some have managed to find new work at other research institutions in Japan (presumably, resetting the 10 year clock), but even when they are able to secure a new position, they will have to join or build a new team, procure new research equipment, and secure funding, setting back their research by months or years.

I live in the United States, and over the past few weeks, I have had to watch mass layoffs at NIH, CDC, NSF, NASA, NOAA, universities, and other science and engineering organizations. So I suppose no government has a monopoly on opportunities to perpetrate arbitrary and pointless acts of cruelty. But whether it’s Japan’s Conversion Rule or DOGE in the United States, these types of actions are the definition of counterproductive and self-destructive. We all have to do better than this.

Situations like the Conversion Rule are not isolated, and the lifetime employment system is being undermined on several fronts. It is becoming more common for regular employees to change jobs, and almost a million people did so in 2024, an increase of more than 60% over the past 10 years [Economist]. In a recent survey, only 21% of young Japanese employees indicated that they plan to stay with their employer until retirement. Younger workers are critical of the seniority-based pay and lifetime tenure that results in “old men that don’t work” (働かないおじさん). These senior staff collect much higher salaries, occupy senior management roles, and limit career growth for younger people. On the other hand, workers in their 40s and 50s may be more spry than the youngsters give them credit; the number of middle-aged job hoppers has increased 6x over the past ten years. A more dynamic workforce is developing, and it suggests significant changes are on the way for legacy institutions.

Japan has accomplished a great deal in science, technology, and engineering over the past 150 years, often with modest resources. These accomplishments have required innovation and technological development, but the key to making them possible has always been the people that envision, invent, and eventually bring the ideas to reality. There were fewer than 9,000 people employed in Japan’s space industry in 2022, a small increase over 2020 and 2021, but a decrease over the employment levels in the mid-1990s and far short of what will be necessary if Japan is to meet its many goals in space over the next decade: multiple advanced remote sensing constellations, a large data analysis industry ecosystem, post-ISS LEO commercial development, lunar exploration, planetary exploration, and, all told, doubling the size of its space industry by the early 2030s. But lofty goals and financial support like the Space Strategy Fund will not be enough. The most important investments will be toward nurturing the current workforce while inviting both young people to enter the field and new entrants joining the field from other industries. They will not just be a “workforce”; they will be thousands of individuals that will need learning opportunities, great teams around them, and thoughtful leadership.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for reading. Please be in touch via LinkedIn with any feedback, questions, comments, or requests for future topics. And if you have a friend or colleague that you think would enjoy JEO, please feel free to share it!

Until next time,

Robert

The bush warbler

Rephrasing itself again

Rephrasing itself

– Fukuda Chio-ni (1703-1775)

鶯や

また言ひなほし

言ひなほし

Uguisu ya

Mata iinaoshi

Iinaoshi