JEO 1 - 2024 Year in Review

Welcome to the first edition of Japan Earth Observer (JEO)

Welcome to Japan Earth Observer

Welcome to the first edition of Japan Earth Observer (JEO), a free monthly newsletter with a news roundup and an in-depth article about the space, Earth observation and geospatial technology industries in Japan. In this edition, I’m going to write a bit about my motivations for the newsletter as well as summarize some major developments in 2024.

First, I should probably introduce myself and explain a bit about why I’ve started this newsletter. I have been working in the geospatial technology world for almost 30 years. I began my technology career doing geospatial data analysis and software development for municipal government in Philadelphia. After a four-year tour of duty in local government, I struck out on my own and started Azavea, a geospatial software engineering company (and a B Corporation) that I would lead and grow over the next 22 years.

But before my geospatial career, I lived and worked in Japan. I had studied Japanese language, history, and culture at the University of Michigan and after I finished my degree, I worked in local government in a small town in Shiga Prefecture as a Coordinator for International Relations, a program operated by the the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). It was an incredible first professional experience, enabling me to improve my Japanese language skills as well as an opportunity to learn about the world of work and to travel broadly in Japan and the rest of Asia. I left Japan in 1994 to attend graduate school in Philadelphia, where I studied Landscape Architecture and received an introduction to geospatial technology.

After more than two decades as the founder and CEO, I sold Azavea in 2023 to Element 84, and following a brief stint as Chief Strategy Officer with them, I found myself on an unplanned sabbatical. I decided to use some of my newly available time to travel, and at the top of my list was spending some time in Japan again. Apart from a brief vacation in Japan more than a decade ago, I had been away for almost 30 years. Being there again was revelatory for me. I found it unexpectedly nourishing and restorative for reasons I cannot entirely explain, and I returned to the U.S. with a conviction that I wanted to find opportunities to more substantively reconnect my life to Japan.

A key challenge, however, is that while I have almost three decades of experience working with geospatial data, software, and Earth observation technology, my geo career has been in North America and in the English language, and I have neither the language nor the context to operate professionally in Japan. My Japanese language skills had slowly seeped back into my head while I was traveling there in 2024, but I had never acquired the vocabulary and context to be able to have meaningful conversations in Japanese about my geospatial technology work. So alongside my newfound conviction - reconnect with my life in Japan - I returned to Philadelphia with a pile of books and a desire to dive back into learning Japanese.

I wrote and spoke on a range of technology and entrepreneurship topics for Azavea and Element 84. This newsletter will be a bit different. Rather than building and growing a business, I hope it will represent part of my effort to combine two components of my professional life: geospatial technology development and Japan. Over my career, I’ve learned that if I really want to understand a topic, it helps me to write about it. The act of trying to explain something to others in written form helps me learn. Further, I have often found that writing helps me think. So that’s what this is, my effort to learn and think through writing. Along the way, I also hope to meet new people, reconnect with long-time colleagues, deepen my understanding on an array of Earth observation topics, and improve my Japanese language skills.

For those of you familiar with my past work, I remain both fascinated and motivated by many of the same themes that drove my work at Azavea: cultivating an open knowledge ecosystem (open data, open source, open science, open standards), building institutions, and applying geospatial technology in service of public good, and this newsletter will likely reflect those interests as well.

Thank you for joining me on this journey.

News & Announcements - 2024 in Review

For this first newsletter, I’m going to highlight a few major 2024 stories from the Japan space and Earth observation ecosystem, but for future editions, I plan to briefly summarize this type of information on a monthly cadence.

Astroscale successfully approaches orbital debris and also goes public

Astroscale, founded in 2013 by Okada Nobu, has had a big year. After a successful launch in February, the ADRAS-J mission tested an innovative spiraling approach orbit to a multi-ton H-IIA rocket upper stage. Unlike most industrial manufacturing endeavors, satellites do not really have an “after-market” whereby the equipment can be supported and maintained after it reaches orbit. That’s both a huge waste (we end up deorbiting satellites that may still have a useful life if they could be refueled) and leaves dangerous debris in orbit to potentially impact and damage other satellites. Astroscale’s ADRAS-J satellite was able to approach within 50m of an uncontrolled rocket body multiple times, observe the debris from close range, and test a collision avoidance system. The ability to safely approach a piece of debris, known as Rendezvous and Proximity Operations (RPO), is a major step toward being able to capture and actively remove orbital debris. The followup contract, to be carried out by ADRAS-J2, was awarded in August and will involve not only RPO but removal and deorbit of the rocket body using a robotic arm. While ADRAS-J was carried out for JAXA under the Commercial Removal of Debris Demonstration (CRD2) program, Astroscale sees a global market for its services and has opened offices in France, Israel, UK and the United States, and Astroscale U.S. has already been awarded a $25.5 million Space Force contract to develop a refueling spacecraft, and the UK Space Agency awarded two contracts this year to Astroscale for the ELSA-M and COSMIC debris removal missions. Astroscale is betting that active debris removal, refueling, life extension, and other services will make them a leader in on-orbit servicing missions. The various contracts mean that it’s already accumulating a good-sized contract backlog.

- ADRAS-J debris approach [Astroscale]

- Astroscale Finalizes Contract for Debris Removal Mission [SpaceNews]

- Satellite refueling concept of operations [SpaceNews]

- Astroscale valued at $1 billion [Nikkei Asia]

- UK Space Agency contract for COSMIC deorbiting mission [Payload]

- Astroscale and ELSA-M design review for de-orbit of OneWeb satellite [SpaceNews]

- Japan is Ground Zero for Space Sustainability [Payload]

- Astroscale IPO [SpaceNews]

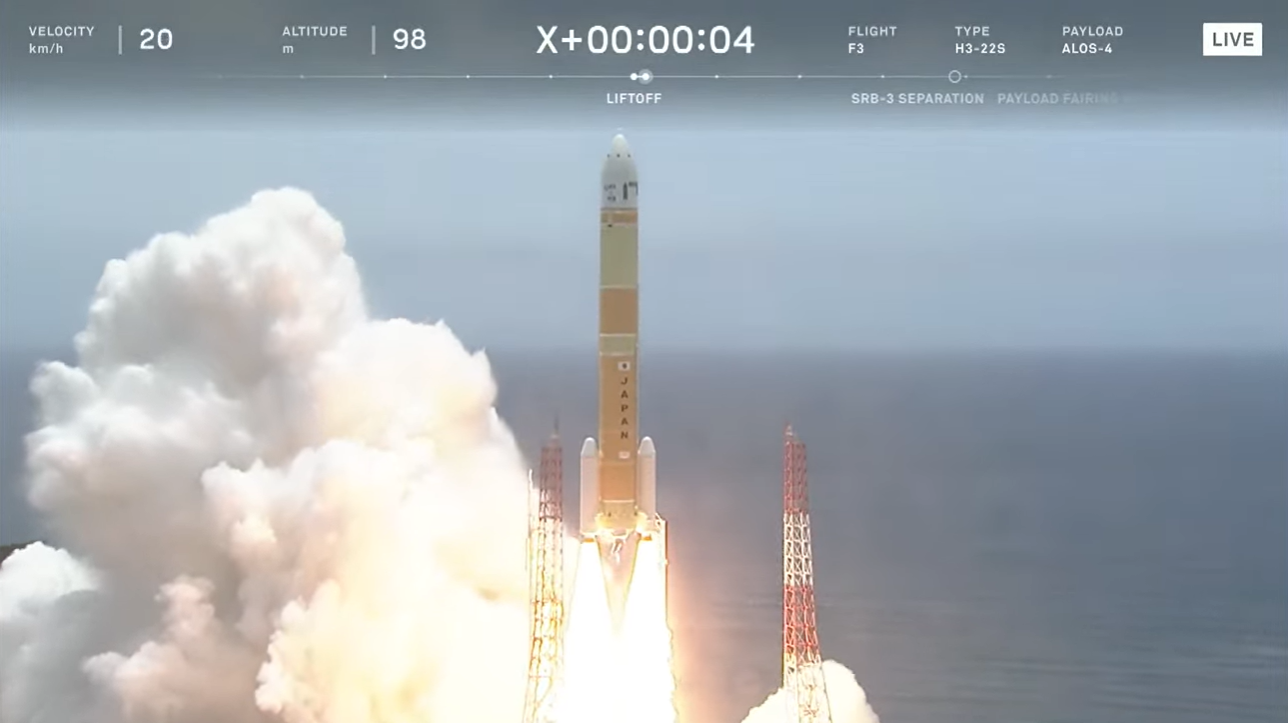

Next generation H3 rockets launch

Japan has been launching satellites to space with solid-propellent rockets since 1958 and liquid-fueled rockets capable of inserting satellites into geostationary orbit since 1975. In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, the United States government forced Japan to license outdated and blackboxed Thor-Delta technology to enable Japan’s early liquid-fueled rockets. The licensing restrictions and black-boxing were naturally irritating to the Japanese government, and Japan set out to build its own sovereign, domestic liquid-fueled rocket design in the 1980’s, The first H-I series rocket was launched from Tanegashima Space Center in August 1986. Subsequent generations of H-II and H-IIA rockets have increased their capacity and capability while also steadily reducing the launch cost. The first test flight of the latest generation H3 rocket in March 2023 failed, destroying the ALOS-3 Earth observation satellite it carried, but 2024 saw the successful second, third, and fourth flights of the new H3 rocket. While it’s not reusable and probably not capable of the Falcon 9’s launch cadence, the H3 has reduced launch costs over previous generations, and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, the primary manufacturer, successfully closed a deals to sell H3 launches scheduled for 2027 to Eutelsat and for the UAE Space Agency’s asteroid mission in 2028. Japan is aiming for 30 launches per year by the early 2030’s. It was a big year for H3.

- H3 is successful on second launch attempt [SpaceNews]

- H3 launches ALOS-4 EO satellite in June 2024 [SpaceNews]

- H3 lofts Kirameki defense comms satellite in Nov 2024 [SpaceNews]

- MHI sells H3 launches to EUTELSAT [SpaceNews]

- UAE buys H3 launch for Asteroid Belt Mission [AGBI]

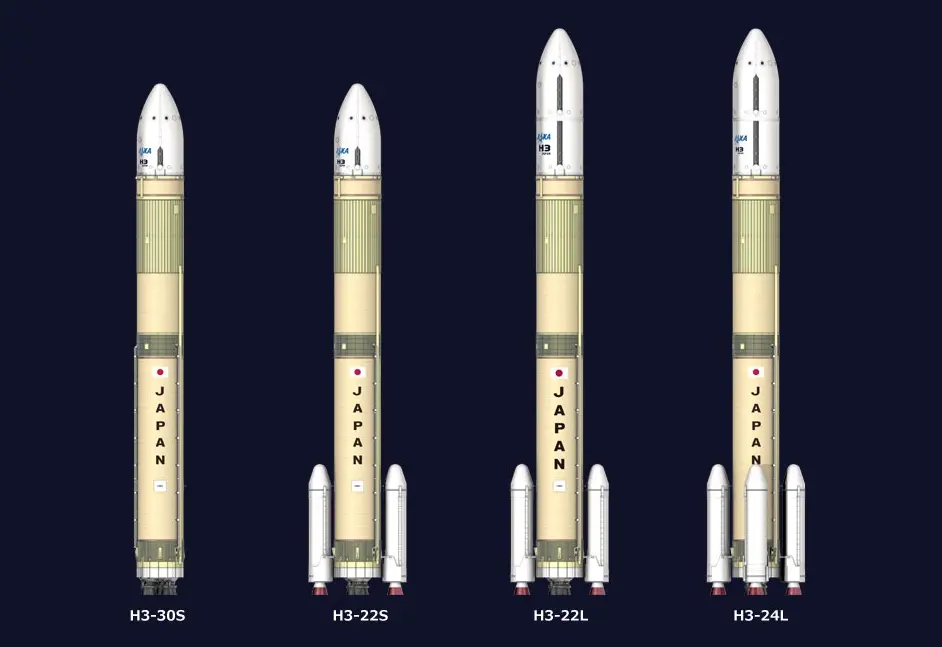

H3 launch vehicle configuration options. Credit: JAXA

Wooden Satellites!

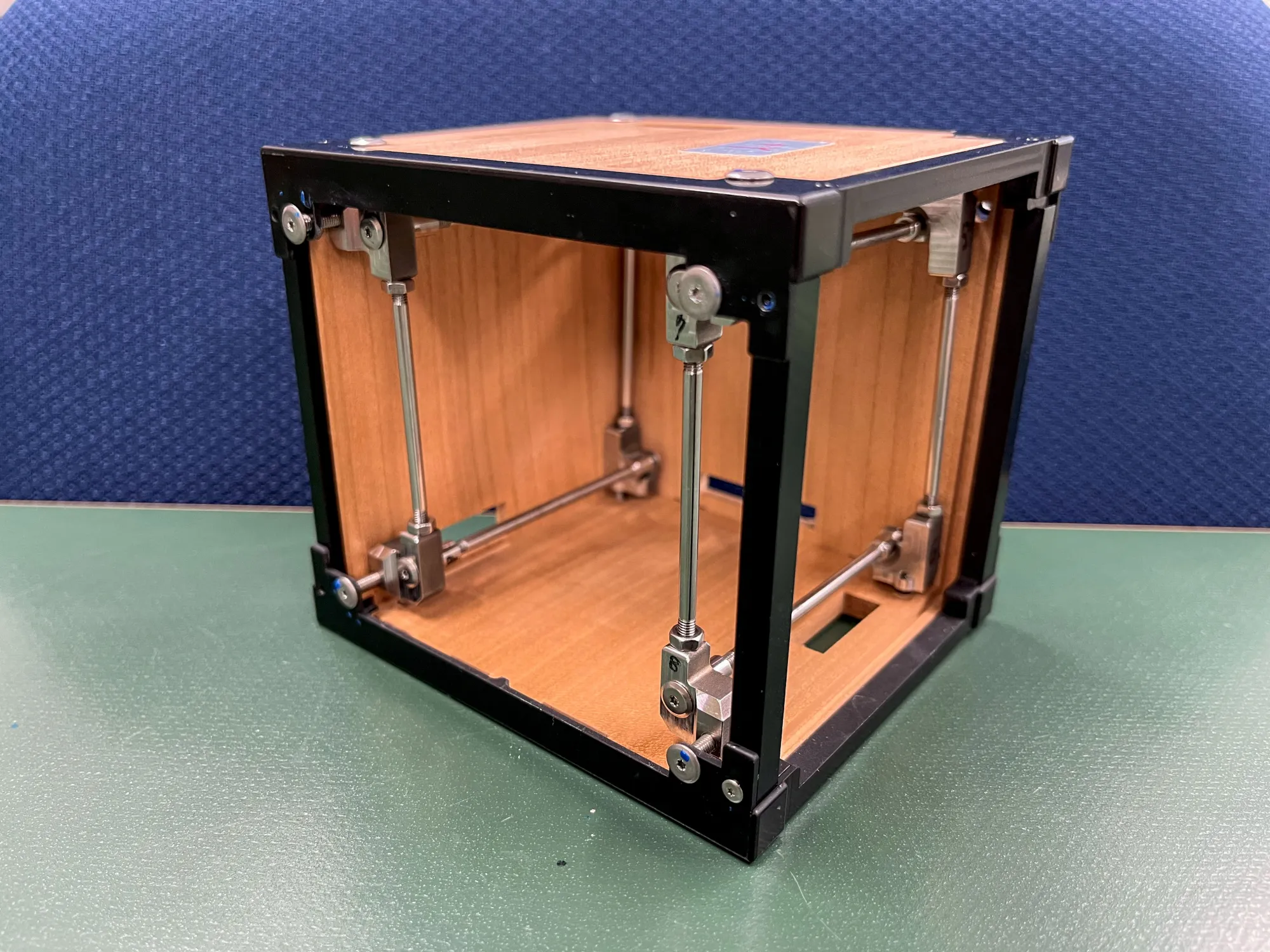

Japan is a land of people who craft amazing things, but building satellites out of wood? They are doing it. Kyoto University and Sumitomo Forestry have built a demonstration satellite in which all of the aluminum parts have been replaced by wood from magnolia trees. Why? There is increasing concern about pollution from metal particles in the upper atmosphere when satellites burn up on reentry. The research team had already sent wood samples for testing different tree species outside the Kibo research module on the ISS. The coffee mug-sized LignoSat (after the Latin word for wood, lignum) is the next step, it was launched to the ISS in November 2024, and it will be deployed from Japan’s Kibo module to test the impact of the orbital environment on the wood components for about six months before reentering the atmosphere. More than 70% of of the Japanese archipelago is covered with forest, and the Japanese people have created amazing things from wood for more than a thousand years. 2025 will see one of the largest wood structures, a huge wood ring building, completed for the Osaka Expo. Japan is also experimenting with using cellulose fibers (e.g. wood) to reduce plastic use in high performance vehicles.

- First wooden satellite [Space.com]

- Japanese Satellite Bets on an Ancient Material: Wood [NY Times]

- 'Grand Ring' by Sou Fujimoto for Expo 2025 Osaka [ArchDaily]

- Japan’s New Wood is Five Times Stronger than Steel [Nikkei Film]

- First Wooden Satellite Deploys from Space [NASA]

Internal view of LignoSat’s structure shows the relationship among wooden panels, aluminum frames, and stainless-steel shafts. Credit: Kyoto University

Mr. Kishida Goes to Washington

Japan was one of the eight founding signatories of the Artemis Accords in October 2000, and JAXA collaboration with NASA and NOAA has been ongoing for decades. But over the past year, Japan-US cooperation on space exploration and research has significantly deepened. The Biden administration has been working hard to cultivate bilateral security and technology relationships with a range of Asia-Pacific nations, and Japan has been a key focus. During an April 2024 visit, Prime Minister Kishida closed several agreements between Japan and the U.S. Under one of these, the “Lunar Surface Exploration Implementing Arrangement’, two Japanese astronauts will be joining future Artemis lunar missions, and, in exchange, Japan is going to contribute a pressurized lunar rover. To that end, JAXA and Toyota unveiled designs for a “Lunar Cruiser” they have been developing over the past five years. The Lunar Cruiser will be able to serve as a pressurized habitat in which astronauts can live for days or weeks at a time. When will it launch? I’d guess the early 2030’s. In addition to ongoing collaboration on the ISS, the Lunar Gateway, and other missions, there was also talk of Japan contributing to NASA’s Dragonfly mission to Titan and the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope as well as NASA contributing to JAXA’s Next-generation Solar-observing Satellite (SOLAR-C).

Other Japan-U.S. discussions in 2024 included efforts to improve defense and space manufacturing supply chain integration, Japan (alongside Poland) joining the Wideband Global Satcom (WGS) military communications infrastructure, and establishment of a U.S. Space Force service component, United States Space Forces – Japan (or, because who doesn’t like unwieldy acronyms: USSPACEFOR-JPN).

It’s hard to say how this will develop under Trump, but both the Artemis Accords and the Artemis lunar program originated during the first Trump administration, and I would guess that much of this collaboration will continue.

- Astronauts and lunar rover agreement [Space.com]

- The U.S. and Japan need more supply chain cooperation [Nikkei Asia]

- Artemis Accords reaches 50 signatories [Space Policy Online]

- Japan and Poland joining Wideband Global Satcom (WGS) [SpaceNews]

Artist's illustration of the planned Toyota/JAXA crewed rover on the moon. Credit: Toyota/JAXA

Japan Collaborates a Lot

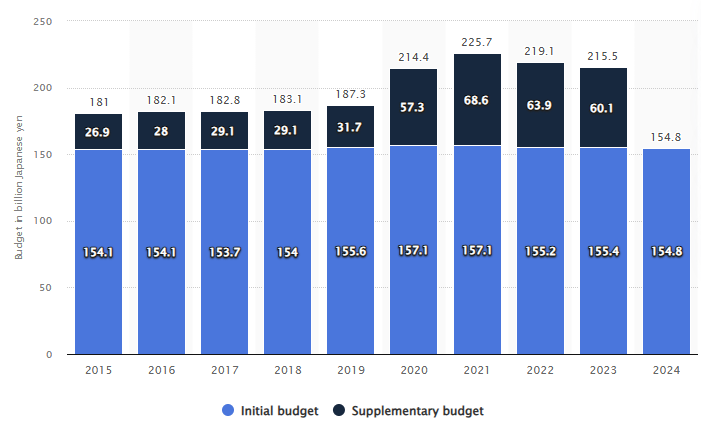

This will probably be an ongoing theme that I’ll highlight periodically: if you are JAXA and you only get ¥154 billion (~$1b at recent exchange rates) for your budget (compare this to €7.8B for ESA and $24.875 billion for NASA), the best way to get things done and increase your impact is probably going to be partnering with others, and Japan has been actively collaborating with NASA, NOAA, ESA, ISRO, and others for decades.

JAXA budget 2015 - 2024. Credit: Stastista

Some contemporary JAXA collaborations include:

- NASA/JAXA XRISM X-ray observatory started yielding some great science [NASA]

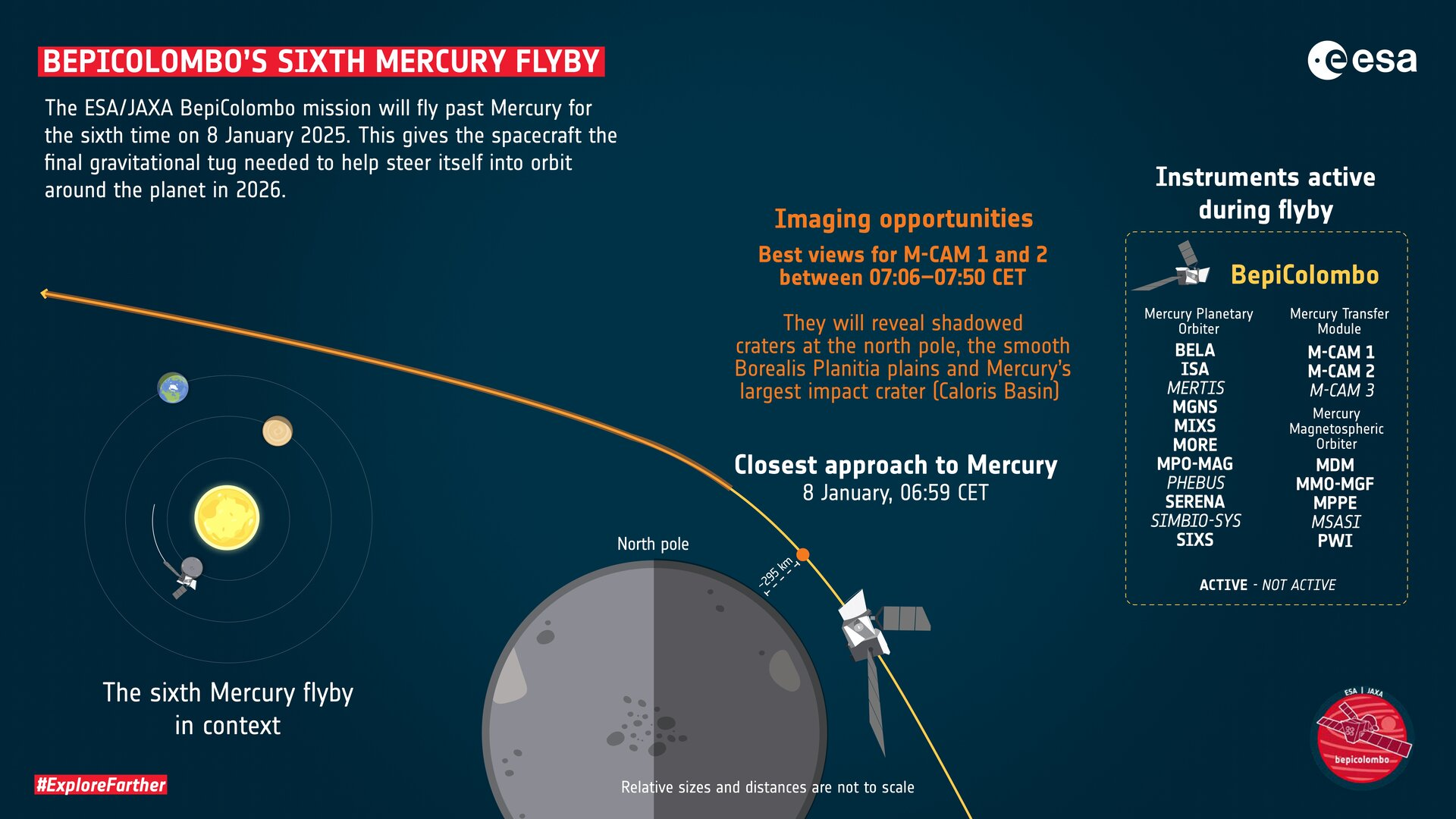

- JAXA/ESA Bepi-Columbo mission just did another flyby in it’s long trip to Mercury

- The ESA/JAXA EarthCARE research mission focused on clouds and aerosols launched in May [ESA]

- Future JAXA and ESA will include asteroid Apophis, mars, moon, and planetary defense [SpaceNews]

- The Lunar Polar Exploration (LUPEX) lander is a collaborative project between ISRO and JAXA. The current plan is for JAXA to provide the H3 launch vehicle and a lunar rover and for ISRO to develop the lander based on the Chandrayaan-3 and Chandrayaan-4 missions. The LUPEX mission is also expected to sport instruments from NASA and ESA.

BepiColombo sixth flyby. Credit: ESA/BepiColombo/MTM

More Moon Stuff

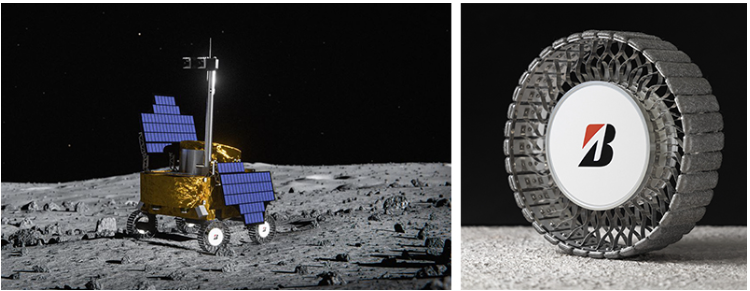

In addition to what I wrote a bit about Japan’s future involvement in the multi-national Artemis program, both JAXA and private Japanese companies are engaged in a range of activities aimed at the Moon. With the Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM) landing on January 19 in Mare Nectaris, south of the Theophilus crater, Japan became the fifth country in history to successfully land on the moon. Despite a late-game thruster failure, the SLIM lander lived up to its "Moon Sniper" nickname and arrived within 50 meters of its planned location, successfully released two small lunar rovers, and then proceeded to survive several months of lunar nights. Japanese startup, ispace (not to be confused with the Chinese space company i-Space), is planning a second moon landing attempt (the first crashed into the moon in April 2023 due to a software error). The Hakuto R mission 2 lander is now in Florida being prepared for a SpaceX Falcon 9 launch in early 2025. It was a busy year for ispace as they also opened a new mission control center in Colorado. Finally, Astrobotic Technology, a U.S. space robotics developer building yet another lunar rover, inked an agreement with Bridgestone to develop a special tire for the CubeRover.

- Japan’s Bet on the World’s Lunar Space Race [Payload]

- SLIM makes pinpoint landing and releases rovers [SpaceNews]

- ispace sets second moon landing attempt [Payload]

- ispace 2nd lunar lander arrives in Florida for early 2025 launch [Space.com]

- ispace sets up Colorado mission control center [ispace]

- Astrobotic rover will have Bridgestone tires [Astrobotic]

Astrobotic rover with Bridgestone tire concept. Credit: Astrobotic

Setbacks

While there have been an array of milestones and accomplishments in the Japan space and Earth observation ecosystem this year, there have also been a number of setbacks as well.

Rockets blowing up

- Space One Kairos: The first flight of the privately developed Japanese rocket, Kairos, built by Space One, ended in failure when the rocket exploded about five seconds after liftoff on March 12, 2024. It was the first attempted launch from a new spaceport on the Kii Peninsula in western Japan. Kairos tried again this week and the rocket lasted longer, but blew up again about two minutes after launch. [Space News] [Space.com]

- Epsilon S booster test: JAXA announced in December 2024 that the launch of the first Epsilon S rocket is unlikely to happen by March 2025 as planned due to a second explosion during ground tests for the second-stage solid-fuel booster. This had followed the first explosion in a test in July 2023. [Asahi Shimbun] [Space.com] [Nippon.com]

Science Spacecraft

- XRISM door is stuck: In January 2024, the X-ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission (XRISM), a JAXA mission with instruments developed in collaboration with NASA, experienced a failure of the aperture door for its Resolve instrument, which prevented the door from opening. While the instrument can still operate, the team decided to put attempts to open the door on hold for 18 months and move forward with the science program as-is. It’s producing good science, but it’s impeded by the door issue. [Space News]

- Plucky Akatsuki Venus mission went silent: Akatsuki (あかつき, 暁, "Dawn") was sent to Venus in 2010 but it’s main thruster failed the planned orbital insertion in December 2010. However, in 2015 JAXA was able to use its attitude thrusters to move it into a highly elliptical orbit around Venus and start its original science mission to study the climate and atmosphere. While it had only a two year planned lifespan, its operation was extended by several years until April 2024, when JAXA lost contact. A Dec 7 X/Twitter message suggested recovery operations are continuing, but it was humanity’s only active mission to Venus, and it’s unclear if it can be recovered. [Ars Technica] [Space.com]

- BepiColombo has a dodgy thruster: The BepiColombo spacecraft, a joint mission between ESA and JAXA launched in 2018, experienced a thruster “glitch” on 26 April 2024, causing a drop in power to the thrusters. Power was restored to 90% capacity by 7 May, but the spacecraft is continuing to operate without its full thrust, and it looks like this will delay its arrival at Mercury from 2025 to November 2026. It has already been a long trip including an Earth flyby, two Venus flybys, and six planned Mercury flybys, all to provide gravity assists. BepiColombo just made its fifth Mercury flyby on 1 December 2024. After a sixth gravity assist, it will make the orbital insertion to Mercury. BepiColombo actually has three components. The Mercury Transfer Module (MTM) is hauling everyone to the planet (and it’s the part with the dodgy thruster). When it arrives, it will release two additional orbiters. The Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) was built by ESA and has eleven instruments (par for the course at ESA, every country and their brother has built an alphabet soup of sensors). The second orbiter, Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO) was mostly built by Japan and has five instruments that will study the plasma, solar wind, dust, and magnetic field around Mercury. Most Japanese missions have a nickname, usually selected from suggestions by the public. The nickname for the MMO is Mio, which means “waterway” and is a nod to the Japanese and Chinese name for Mercury, the “water star” (水星) [Space.com]

Cybersecurity Breaches

After revelations in 2023 of major cybersecurity breaches and mishandling of classified documents in the Ministry of Defense, JAXA revealed it had also suffered a series of cyberattacks beginning in June 2023. Hackers initially stole the personal data of approximately 5,000 JAXA personnel and employees from partner companies (including NASA, Toyota Motor Corp., Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd. and the Defense Ministry) and then used that information to access the Microsoft 365 accounts of JAXA executives. More than 10,000 Microsoft Office files may have been stolen. JAXA said that no sensitive information related to national security or rocket technologies was lost, but it’s not a good look for JAXA. [Nikkei Asia] [Asahi Shimbun]

These setbacks represent significant challenges for Japan's space and Earth observation programs, but it is important to note that the Japanese space program has a history of resilience and innovation, and it is likely that they will be able to overcome these challenges and continue to make significant contributions.

AI and Japan in 2024

Ok, so AI is not necessarily space and Earth observation, the topic of this newsletter. But I’m going to include it here as I think AI technology developments will have a significant impact on data processing of geospatial data transferred from Earth observation constellations. Further, at least one Japanese firm is a current leader in the development of a foundation geospatial model.

If you only read the technology news in Europe and North America, you could easily come to the conclusion that all of the major developments in AI are all happening at Anthropic, OpenAI, Google, and Meta. That would be a mistake. In addition to significant progress at Chinese firms like O1.AI creating high quality AI models at low cost, Japan is attracting significant investment from US tech firms, and Japanese firms, like Sakana, are both pioneering new AI model development approaches and raising substantial funds to compete at the global level. First, the investments from abroad. On the heels of significant investments by AWS (more than $15 billion!), Google, Microsoft, NVIDIA, and Meta, OpenAI announced significant investments in both improving the speed of its Japanese language processing and creating a Tokyo subsidiary that will enable it to address local market needs. All told, U.S. tech firms have announced data center and AI-related investments of more than $26 billion in Japan. But while these massive investments will no doubt bolster the economy, they also carry the potential for increased dependence on U.S. digital technology. Japan continues to enjoy a trade surplus in manufactured goods, but it imports far more digital goods (everything from streaming media to cloud computing) than it exports, and the 2024 digital trade deficit was more than double that in 2015, rising to $ 33 billion. Thus far, the Japanese government has had a relatively light regulatory approach to AI and has actively courted foreign AI investment as well as supporting development of domestic capabilities. AI is seen as a key long-term mechanism to counter the impact of labor shortages from the declining population as well as a way to leverage long-term and ongoing investments in SE Asia.

In addition to data centers. U.S., EU, Chinese, and Japanese firms are all investing in performance improvements to generative AI models for the Japanese language. The intricate writing system, lack of white space, and vibrant digital culture (emoji and kaomoji both originated in Japan) add complexity to LLM development and specialized evaluation systems and leaderboards have been created over the past year to test and measure model performance.

Lastly, the domestic AI action. Tokyo-based R&D startup, Sakana AI, has raised $200 million to support AI model development in service of scientific discovery. Many of its Series A investors are Japanese companies, and catalyzing a domestic Japanese AI ecosystem is an explicit company objective. This will require investment in expanding the domestic AI talent pool as well as cultivation of an AI research community in Japan. Sakana’s initial year has focused on applying “nature-inspired” approaches to foundation model development, such as combining thousands of existing AI models to “evolve” better composite models through “crossover” and “mutation”. Most of the leading AI firms have been focused on building ever-larger AI models, improving performance but also incurring exponentially greater computing, energy, and financial cost. Rather than developing large models, Sakana aims to evolve a “diverse swarm of niche models” as a more sustainable path (e.g. less energy, less compute) to creating advanced AI agents. In August, Sakana announced AI Scientist, a system for automating scientific discovery, from idea generation to iterative experimentation, paper writing, and paper evaluation. They also have a great blog and regularly publish in both English and Japanese.

Sakana is not the only domestic AI story that caught my eye in 2024. Degas is a Tokyo-based financial services firm that pairs smallholder farmer financing with training, tools, and practices that increase yields and encourage regenerative agriculture, thereby improving soils over time. Though based in Tokyo, most of their employees work directly with farmers in Ghana. They have gradually invested in mobile software, remote sensing data, and, recently, geospatial foundation AI models that enable them to improve the resources they can provide to farmers. It is entirely too common for a cool technical innovation to be developed for its own sake and only later are real-world applications considered; this has certainly been true for satellite remote sensing constellations, and I think many AI investments continue to search for business value proportional to their investment. I see Degas as a rare example of a firm for which the product or service came first, and the geospatial and AI technology are a means to that end. Efforts like Clay and the NASA/IBM Prithvi geospatial models have received a lot of attention, but Degas has quietly built a world-leading geospatial AI model by focusing on delivering value to its customers, smallholder farms in Africa, and they now have a model that can be applied to other geospatial applications as well.

- AWS, Google, and Microsoft increase data center investments in Japan [Nikkei Asia] [CloudPro]

- Japan is light on AI regs [Nikkei Asia]

- OpenAI is invests in tripling Japanese language performance [Nikkei Asia]

- Japanese Language LLM Leaderboards

- Open Japanese LLM Leaderboard on HuggingFace [About] [Leaderboard]

- Nejumi LLM Leaderboard Neo [Leaderboards, graphs, and explanation]

- Japan to help SE Asia with AI [Nikkei Asia]

- Fujitsu investing in OpenAI rival [Nikkei Asia]

- Sakana raises $200 million to fund alternative AI approach [Nikkei Asia]

- Degas uses generative AI on AWS to help smallholder farmers in Ghana [AWS re:invent]

Asia-Pacific Conferences & Events

While I’m mostly focused on Japan in this newsletter, I’d like to highlight some events across the Asia-Pacific region as well as those in Japan.

- International Space Industry Exhibition (ISIEX), 29 - 31 January 2025 - Tokyo Big Sight - Nikkan Kogyo Shimbun - this event had 20,000 visitors in 2024 -

- Global Space Technology Convention & Exhibition 2025 (GSTC) - 26 - 28 February 2025 Singapore

- FOSS4G Hokkaido, 14 February 2025, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan

- State of the Map Japan - 15 February 2025, 1p - 6p, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan

- India Space Congress - 27-27 June 2025 - New Delhi, India

- Spacetide - 7 - 10 July 2025 - Toranomon, Tokyo, Japan

- 35th International Symposium on Space Technology and Science (ISTS) & 14th Nano-Satellite Symposium (NSAT) Joint Symposium - 12 - 18 July 2025 - Asti Tokushima, Japan

A bee

staggers out

of the peony

– Matsuo Basho (1644-1694) - translated by Robert Hass

牡丹蘂深く

分け出づる蜂の

名残り哉

botan shibe fukaku

wake izuru hachi no

nagori kana